Target audience: Intermediate

Estimated reading time: 7'

Newsletter: Geometric Learning in Python

Choosing between Riemannian and Euclidean metrics for classifying signal or dense data can be challenging. This article offers engineers an easy method to select the most suitable metric using the pyRiemann library.

What you will learn: How to determine the suitable metric for a given dataset to optimize the decision boundary and accuracy for any classifier.

Notes:

- Environments: Python 3.11, pyRiemann 0.6, mne 1.7.1, SciKit-learn 1.5.1, Matplotlib 3.9.1

- This article assumes that the reader is somewhat familiar with Riemannian geometry [ref 1, 2].

- Source code is available at Github.com/patnicolas/Data_Exploration/classifiers

- To enhance the readability of the algorithm implementations, we have omitted non-essential code elements like error checking, comments, exceptions, validation of class and method arguments, scoping qualifiers, and import statements.

Introduction

Geometric learning tackles the challenges posed by scarce data, high-dimensional spaces, and the requirement for independent representations in the creation of advanced machine learning models. The fundamental aim of studying Riemannian geometry is to comprehend and scrutinize the characteristics of curved spaces, which are not sufficiently explained by Euclidean geometry alone.

This article is the 11th installment in our ongoing series on geometric learning. Most articles in this series use the Geomstats differential geometry library to implement some of the most common machine learning algorithms on the hypersphere.

In this post, we use pyRiemann [ref 3], a Python library dedicated to signal processing and time series analysis on Riemannian manifolds.

The two most common Riemann metric for SPD matrices are:

- Affine-Invariant metric

- Log-Euclidean metric

These two metrics have been described and evaluated in a previous post: [ref 4]

Symmetric positive definite (SPD) manifold

SPD matrices have been introduced in a previous article in Logistic Regression on Riemann Manifolds

A square matrix A is symmetric if it is identical to its transpose, meaning that if a are the entries of A, then aaij. This implies that A can be fully described by its upper triangular elements.

A square matrix A is positive definite if, for every non-zero vector b, the product >= 0 [ref 5].

If a matrix A is both symmetric and positive definite, it is referred to as a symmetric positive definite (SPD) matrix. This type of matrix is extremely useful and appears in various real-world applications. A prominent example in statistics is the covariance matrix, where each entry represents the covariance between two variables (with diagonal entries indicating the variances of individual variables). Covariance matrices are always positive semi-definite (meaning ), and they are positive definite if the covariance matrix has full rank, which occurs when each row is linearly independent from the others.

The collection of all SPD matrices of size forms a manifold.

pyRiemann library

pyRiemann is a Python machine learning package built on the scikit-learn API. It offers a high-level interface for classifying real or complex-valued multivariate data using the Riemannian geometry of symmetric positive definite (SPD) and Hermitian positive definite (HPD) matrices.

Its primary aim is to conduct multivariate data analysis on time series within these Riemannian manifolds. Our use case consists of comparing various known machine learning algorithms in Euclidean and Riemann space (SPD matrices). The data sets consists of signals such as Electroencephalograms (EEG) or Magnetic Resonance Images (MRI) used in brain-computer interface (BCI) and required mne library to be loaded.

Setup

The installation and configuration of pyRiemann is straight forward [ref 6].

To Install pyRiemann module: pip install pyriemann

To install mne: pip install mne

Source from Github: git clone https://github.com/pyRiemann/pyRiemann.git

Datasets

We are comparing two widely used machine learning algorithms, Support Vector Machine (SVM) and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), for Symmetric Positive Definite matrices in Euclidean space (using Scikit-learn) and on a Riemannian manifold. The comparison will be conducted using two datasets:

- Set 1: Data from Electroencephalograms (Brain-Computer Interface) [ref 7]

- Set 2: Synthetic Gaussian distributed data

Let's encapsulate the data generation process within a class named SPDMatricesDataset. We consider a sample of 48 SPD matrices, with target values defined as binary {0, 1}. The create method generates the two datasets described in the previous section.

Note: Some methods and variables that are not essential for understanding the algorithms have been omitted.

class SPDMatricesDataset(object):

def __init__(self) -> None: n_spd_matrices = 48

self.target = np.concatenate([

np.zeros(n_spd_matrices), np.ones(n_spd_matrices)

])

# Generation of data sets used in comparing SVM and kNN # over Euclidean space and Riemannian manifold

def create(self) -> List[np.array]: evals_lows = 11 class_sep_ratio = 1.0

spd_matrices = self.__make_spd_matrices(evals_lows)

return [

(spd_matrices, self.target), # Set 1

self.__make_gaussian_blobs(class_sep_ratio), # Set 2

]

The two data sets are visualized with scatter plots using matplotlib module.

Finally, the method train_test_data_split extracts the training and test data from the features and target data, and encapsulate them into the SPDTrainingData data class (see Appendix).

@staticmethod

def train_test_data_split(features: np.array, target: np.array) -> SPDTrainingData:

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

train_X, test_X, train_y, test_y = train_test_split(

features,

target,

test_size=0.3,

random_state=42

)

return SPDTrainingData(train_X, test_X, train_y, test_y)Evaluation

The evaluation of the two metrics (Euclidean and Riemannian) for any given classifier involves two steps:

- Calculate the classifier's score for both metrics.

- Define the decision boundary for each of the two datasets.

Implementation

We encapsulate the evaluation of these metrics within a class named SPDMatricesClassifier. Training and scoring the classifier on the two datasets utilize the pyRiemann API [ref 8], which conveniently follows the method signatures of Scikit-learn's equivalent functions.

class SPDMatricesClassifier(object):

def __init__(self,

classifier,

spd_metric: SPDMetric,

spd_training_data: SPDTrainingData) -> None:

self.classifier = classifier # Target classifier (SVM,...)

self.spd_metric = spd_metric # Metric (Euclidean, ...

self.spd_training_data = spd_training_data # Our training data

# Train then score the given classifier using pyRiemann API

def score(self) -> float: # 1. Select metric

self.classifier.set_params(**{'metric': str(self.spd_metric.value)})

# 2. Train model

self.classifier.fit(self.spd_training_data.train_X, self.spd_training_data.train_y)

# 3. Score model on the test data return self.classifier.score(

self.spd_training_data.test_X,

self.spd_training_data.test_y)

@staticmethod

@partial(np.vectorize, excluded=['clf'])

def get_probability(cov_x: np.array, cov_y: np.array, cov_z: np.array, clf):

cov = np.array(

[[cov_x, cov_y, 0.0, 0.0], [cov_y, cov_z, 0.0, 0.0], [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0], [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]]

)

u = cov[np.newaxis, ...]

return clf.predict_proba(u)[0, 1]Scoring

The score is computed on the test data and target from a sample of 48 SPD matrices

K-Nearest Neighbors (k=4)

Euclidean

Set 1: 0.827

Set 2: 0.655

Riemann -

Set 1: 0.896

Set 2: 0.689

Support Vector Machine

Euclidean

Set 1: 0.965

Set 2: 0.697

Riemann

Set 1: 1.000

Set 2: 0.586

As expected, both k-Nearest Neighbors and Support Vector Machines achieve higher scores on the Riemannian manifold for SPD matrices.

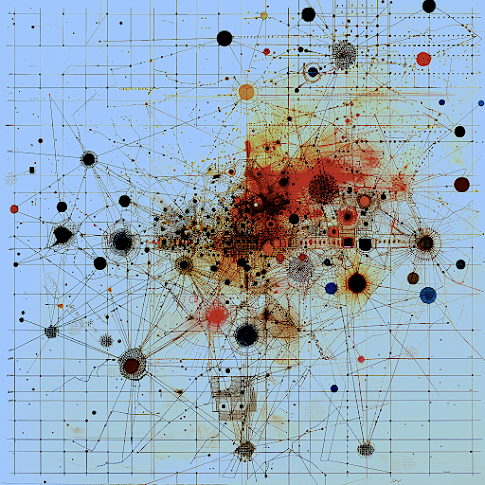

Classifier decision boundary

The objective is to evaluate the decision boundary between target values {0, 1} for classifying the two datasets using a support vector machine with both Riemannian and Euclidean metrics. The input parameters consist of 48 SPD matrices, a range [11, 15] for displaying decision boundary with a class separation of 1.0

Dataset 1 (SPD matrices)

Fig. 3 Decision Boundary Support Vector Machine - Euclidean space

Fig. 4 Decision Boundary Support Vector Machine - Riemann Manifold

Dataset 2 (Synthetic Gaussian)