Estimated reading time: 7'

- Environment: Python 3.11, Numpy 1.26.4, Geomstats 2.7.0, Matplotlib 3.8.2

- This article is a follow up to Foundation of Geometric Learning

- Source code available at Github.com/patnicolas/Data_Exploration/manifolds

- To enhance the readability of the algorithm implementations, we have omitted non-essential code elements like error checking, comments, exceptions, validation of class and method arguments, scoping qualifiers, and import statements.

Geometric learning

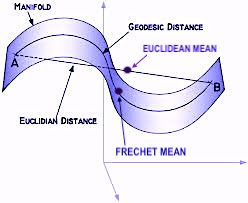

- Understanding data manifolds: Data in high-dimensional spaces often lie on lower-dimensional manifolds. Differential geometry provides tools to understand the shape and structure of these manifolds, enabling generative models to learn more efficient and accurate representations of data.

- Improving latent space interpolation: In generative models, navigating the latent space smoothly is crucial for generating realistic samples. Differential geometry offers methods to interpolate more effectively within these spaces, ensuring smoother transitions and better quality of generated samples.

- Optimization on manifolds: The optimization processes used in training generative models can be enhanced by applying differential geometric concepts. This includes optimizing parameters directly on the manifold structure of the data or model, potentially leading to faster convergence and better local minima.

- Geometric regularization: Incorporating geometric priors or constraints based on differential geometry can help in regularizing the model, guiding the learning process towards more realistic or physically plausible solutions, and avoiding overfitting.

- Advanced sampling techniques: Differential geometry provides sophisticated techniques for sampling from complex distributions (important for both training and generating new data points), improving upon traditional methods by considering the underlying geometric properties of the data space.

- Enhanced model interpretability: By leveraging the geometric structure of the data and model, differential geometry can offer new insights into how generative models work and how their outputs relate to the input data, potentially improving interpretability.

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks: Projecting physics law and boundary conditions such as set of partial differential equations on a surface manifold improves the optimization of deep learning models.

- Innovative architectures: Insights from differential geometry can lead to the development of novel neural network architectures that are inherently more suited to capturing the complexities of data manifolds, leading to more powerful models.

Differential geometry basics

Geomstats library

- geometry: This part provides an object-oriented framework for crucial concepts in differential geometry, such as exponential and logarithm maps, parallel transport, tangent vectors, geodesics, and Riemannian metrics.

- learning: This section includes statistics and machine learning algorithms tailored for manifold data, building upon the scikit-learn framework.

Use case: Hypersphere

Components

- id A label a point

- location A n--dimension Numpy array

- tgt_vector An optional tangent vector, defined as a list of float coordinate

- geodesic A flag to specify if geodesic has to be computed.

- intrinsic A flag to specify if the coordinates are intrinsic, if True, or extrinsic if False.

# --- Code Snippet 1 ---

@dataclass

class ManifoldPoint:

id: AnyStr

location: np.array

tgt_vector: List[float] = None

geodesic: bool = False

intrinsic: bool = False # --- Code Snippet 3 ---import geomstats.visualization as visualization

from geomstats.geometry.hypersphere import Hypersphere, HypersphereMetric

from typing import NoReturn, List

import numpy as np

import geomstats.backend as gs

class HypersphereSpace(object):

def __init__(self, equip: bool = False, intrinsic: bool=False):

dim = 2

super(HypersphereSpace, self).__init__(dim, intrinsic)

# Geomstats hypersphere self.space = Hypersphere(dim=self.dimension, equip=equip, intrinsic= intrinsic) self.hypersphere_metric = HypersphereMetric(self.space)

def belongs(self, point: List[float]) -> bool:

return self.space.belongs(point)

# Simple uniform sampling

def sample(self, num_samples: int) -> np.array:

return self.space.random_uniform(num_samples)

def tangent_vectors(self, manifold_points: List[ManifoldPoint]) -> List[np.array]:

def geodesics(self,

manifold_points: List[ManifoldPoint],

tangent_vectors: List[np.array]) -> List[np.array]:

def show_manifold(self, manifold_points: List[ManifoldPoint]) -> NoReturn:

- belongs to test if a point belongs to the hypersphere

- sample to generate points on the hypersphere using a uniform random generator

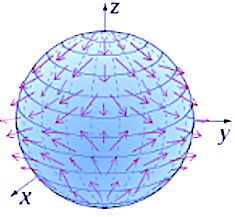

Tangent vectors

# --- Code Snippet 4 ---

def tangent_vectors(self, manifold_points: List[ManifoldPoint]) -> List[np.array]:

def tangent_vector(point: ManifoldPoint) -> (np.array, np.array):

import geomstats.backend as gs

# Create a tangent vector at the given point on the Manifold

vector = gs.array(point.tgt_vector)

tangent_v = self.space.to_tangent(vector, base_point=point.location)

# Compute the end point using the exponential map G(1) =exp_P(v) end_point = self.hypersphere_metric.exp( # 2 tangent_vec=tangent_v, base_point=base_pt ) return tangent_v, end_point

return [self.tangent_vector(point) for point in manifold_points] # 1

# --- Code Snippet 5 ---

manifold = HypersphereSpace(equip=True)

# Uniform randomly select points on the hypersphere

samples = manifold.sample(3)

# Generate the manifold data points

manifold_points = [

ManifoldPoint(

id=f'data{index}',

location=sample,

tgt_vector=[0.5, 0.3, 0.5],

geodesic=False) for index, sample in enumerate(samples)]

# Display the tangent vectors

manifold.show_manifold(manifold_points)

Geodesics

# --- Code Snippet 6 ----def geodesics(self,

manifold_points: List[ManifoldPoint],

tangent_vectors: List[np.array]) -> List[np.array]:

def geodesic(manifold_point: ManifoldPoint, tangent_vec: np.array) -> np.array:

return self.hypersphere_metric.geodesic(

initial_point=manifold_point.location,

initial_tangent_vec=tangent_vec

)

return [geodesic(point, tgt_vec)

for point, tgt_vec in zip(manifold_points, tangent_vectors) if point.geodesic]